[Editor’s note: We welcome back contributing writer and longtime friend Ryan Reft. He’s kindly allowed us to repost this essay from his groupblog Tropics of Meta. For some of his past contributions to CultFootball see here, here and here.]

Over the past fifteen to twenty years, historians have increasingly emphasized the role of sports as both a driver and reflection of society. The recent Bill Simmons-inspired and ESPN-produced 30 for 30 documentary series tackled a number of difficult subjects via sport. In “The Two Escobars“, directors Jeff and Michael Zimbalist travelled through 1980s Columbia, following the lives of Pablo (international drug dealer/murder/local philanthropist) and Andres Escobar (captain of Columbia’s 1994 World Cup team murdered in a nightclub alteration several months later). The two unrelated protagonists encapsulated the travails of late 20th century Columbia. Drug money filtered into the nation’s soccer infrastructure, boosting its competitive success but also adding layers of complexity and violence to a nation already struggling with decades of conflict. Writing for the Onion’s AV Club, Todd VanDerWerff summarized its importance similarly: “The film’s portrayal of Colombia as a nation that made its compromises and learned to live with the hell they unleashed is also particularly good, as the story of the two men at the center slowly radiates outward to encompass more and more of the nation’s society.”

This is not a wholly unusual conclusion for the series. In “Pony Exce$$,” director Thaddeus Matula explored the corruption and ultimate destruction of Southern Methodist University’s (SMU) then dominant football program as booster money flowed in from the oil wealth that defined the Southwest US in the 1980s. Though the Southwestern Conference consisted of eight schools (Baylor, Rice, SMU, Texas, Texas Tech, Texas A&M, Arkansas, and Texas Christian University), Dallas served as a hub for numerous successful graduates of each school. As several observers note in the documentary, football rivalries crackled in the board room meetings of Dallas high rises as alumni from all schools engaged in recruiting practices that seemed to define the decade.

Likewise, Billy Corben’s film,“The U” about the dominance and bravado of Miami University’s 1980s football teams reflects similar themes. Miami’s football team served to unite a divided city behind a collection of local talent that also rewrote the rules of the game. Miami’s players excelled spectacularly on the field but stoked controversy with their trash talk and exuberance. If oil money shaped SMU, Miami’s notoriously tough African American neighborhoods, embraced by Miami’s first successful coach Howard Schnellenberger, came to symbolize “The U’s” power. Along with cultural productions like Scarface, Miami Vice and the notorious Two Live Crew, players like Michael Irvin challenged college football and its fans. Unlike “Pony Exce$$”, “The U” reveals the racial undertones that marked some of the criticism faced by the Miami program. When teamed with Steve James’ masterful “No Crossover: The Trial of Allen Iverson” and the recent “Fab Five” film about the innovative early 1990s Michigan basketball team, “The U” reveals so much more about American life than just college football. Race, money, and a changing cultural landscape collided. As one writer observed, James’ movie looks at Allen Iverson “more as a phenomenon, a human inkblot whose polarizing effect on people often says more about them than it does about him. They see whatever they want to see, and that may or may not be the truth.” In essence, all these films and others in the 30 for 30 series function to elevate sports to a level of political and social importance that might have been derided in early decades.

“Architecture is the simplest means of articulating time and pace of modulating reality and engendering dreams. It is a matter of not only of plastic articulation and modulation expressing an ephemeral beauty, but of a modulation of producing influences in accordance with the eternal spectrum of human desires and the progress in fulfilling them. The architecture of tomorrow will be a means of modifying present conceptions of time and pace. It will be both a means of knowledge and a means of action.” – Ivan Chtcheglov, Forumulary for a New Urbanism, 1953

Writing in 1953, nineteen year old architect and devotee of the Situationist movement, Ivan Chtcheglov published his sweeping indictment of mid-century urban planning. For Chtcheglov, the architecture of cities past reflected the dead life of capitalist production. City dwellers had been hypnotized by the built environment, thus, focusing exclusively on capitalist accumulation to the extent that when “presented with the alternative of love or a garbage disposal unit, young people of all countries have chosen the garbage disposal.” One can see parallels with sport, most clearly in the above examples regarding SMU and the Escobars. The excess capital of drug and oil money created a vehicle for the egos and dreams of ruling classes that were then imposed. (To be fair, soccer teams as several interviewees in The Two Escobar note, serve as great money laundering devices. One might suggest the same of Enron and other corporate entities in recent years.)

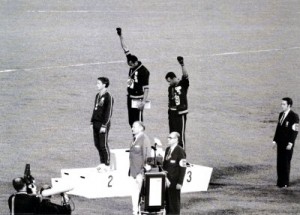

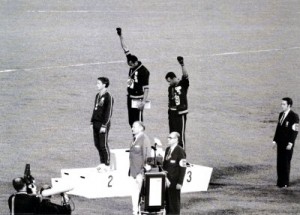

For Americans, sports provided both meaningless entertainment and incredible important cultural moments of resistance. Dave Zirin documents athlete resistance of the twentieth century in his 2005 work, What’s My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States. To Zirin’s credit, What’s My Name, Fool? gathers countless examples of political acts by athletes across the sports spectrum, engaging in issues of race, gender, and class. For example, Zirin traces the complicated politics of Jackie Robinson who, despite his bravery in desegregating MLB, came to be unfairly seen by radical Black nationalists of the late 1960s as a sell out. Some have described Zirin as sort of Howard Zinn of spors journalism. Perhaps. He does look at major historical events like the 1968 Mexico City Olympic protest by Tommy Smith and John Carlos, in which both athletes upheld closed black gloved fists. Zirin explores many facets of the event that had gone unnoticed. Unfortunately, while Zirin collects valuable stories worth reflection, he too often veers in the direction of soap box oratory. Moreover, Zirin seems to feel the need to conclude paragraphs with zingers. For example, how about this gem regarding the failure of several WNBA sports franchises: “while some franchises found success, others have folded faster than a rib joint in Tel Aviv.” (186) When discussing Allen Iverson, Zirin notes Iverson’s role as an anti-corporate anti-hero summarizing his nickname may have been A.I. but “there was nothing artificial about him.” (163) Nuance is not the most prominent feature of What’s My Name, Fool. Still, even if the equivalent of street corner radical, Zirin contributes something to our knowledge of American culture and sport.

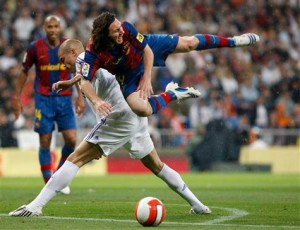

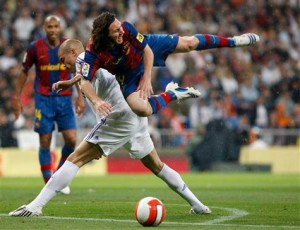

If baseball and to a lesser extent American football and basketball have served as venues for political expression, predictably, football occupies a similar position for Europeans. In How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin Foer traipses through countries around the world, but predominantly Europe, exploring the meanings and processes that manifest themselves in the sport. Throughout How Soccer Explains the World one thing becomes clear, the political complexity of football and more generally, sport, radiates in countless directions. When Foer presents Barcelona’s “bourgeois nationalism” as a model for 21st century cosmopolitanism, he goes so far as to claim that it “redeems the concept of nationalism.” (198) For Foer, Barca never demonizes opponents the way supporters at Red Star (Belgrade- the subject of a previous chapter, one that found soccer fan bases and clubs of the former Yugoslavia as germs for the paramilitary organizations of the Balkan wars in the 1990s) have. Instead, Barca illustrates that “fans can love a club and a country with passion and without turning into a thug or terrorist.” (197)

A central aspect of Barca’s identity rests on its foundational myth, its role as a means of Catalan resistance toward the post Spanish Civil War fascist Franco regime. According to this myth, Camp Nou, Barca’s legendary stadium, enabled Catalan fans to express themselves in ways forbidden by Franco. Camp Nou allowed for political and social subversiveness. “Its fans like to brag that their stadium gave them a space to vent their outrage against the regime,” writes Foer. “Emboldened by 100,000 people chanting in unison, safety in numbers, fans seized the opportunity to scream things that could never be said, even furtively, on the street or in the café.” (204) Yet, as Foer acknowledges, there is another way to view Barca’s history. More likely, Franco saw Camp Nou and Barca as harmless outlets for his repressed populations. Unlike the Basque region and its terrorist/separatist movement ETA, Catalonia never developed any similar liberation fronts.