In a recent podcast for Grantland, Roger Bennett and Roger Davies reflected on MLS’s current fortunes. After nearly two decades, they argued, the league had made it through the leanest years intact, financially healthy, and ready to expand its market share. Indeed, soccer remains one of the nation’s most popular youth sports and perhaps more importantly, among 17 – 24 year olds, as was widely reported last year, soccer ranks second just behind American football in popularity. Undoubtedly, as evidenced by their recent success in the English Premiership, American players, most of them former or current MLS standouts, have become increasingly common. From grunge era throwback Brek Shea’s recent debut for and Geoff Cameron’s starting role in Stoke City’s side, Clint Dempsey and Stuart Holden’s (when healthy) long standing runs, and Landon Donovan’s past successes at Everton not to mention Jozy Altidore’s 24 goals for AZ Alkmaar in the Netherlands, the skill level of American players in MLS has risen to the extent European clubs now see promise. Indeed, if one watched the raucous March 3 Portland Timbers/NJ Red Bulls home opener, a cracker of a 3-3 draw, one would think MLS had arrived.

Yet, during halftime of Sunday night’s fixture in Portland, ESPN soccer analysts Taylor Twellman and Alexi Lalas delved into one of the few non-Landon Donovan controversies/talking points of the new season: Chivas USA and their apparently pro-Mexican/Latino recruiting model. The two former US national team members highlighted Chivas’ recent commitment to building the team’s ties to Mexico by openly recruiting and signing Latino, often Mexican, surnamed players. Lalas lamented to Twellman that though the policy fell short of racism it remained “exclusionary.” Though league President Don Garner supported Chivas’ efforts – “We need teams that look and feel different,” he told Lalas – the two analysts clearly disagreed with the commissioner’s policy. “Here’s my question for Don Garner.” Lalas began. “If you were a young boy playing soccer in Southern California and you don’t have Mexican or Hispanic heritage, do you have an equal opportunity to play for both your teams in Los Angeles and right now the answer is no and I don’t know if this is the message the league wants.” As Cultfootball co-editor Suman Ganguli commented in an email exchange with fellow football bloggers, “I think Lalas just played the white man’s burden race card …. Amazing.” Ganguli along with fellow CF editor Sean Mahoney sketched out the perfect film treatment for America’s first MLS oriented movie:

Johnny Football (Futbol?) toiling away in the hot SoCal sun on beautifully manicured fields (thanks to those illegal landscapers working the sprinklers), housekeeper washing his training kits. Just hoping to make it to the big leagues someday (or at least one of the local MLS sides). Maybe use his signing bonus to buy his parents a (2nd) house, say a nice little ski cabin in Mammoth.

As noted by Ganguli, the film’s narrative arc already had its trademark song lined up, Frank Ocean’s “Sweet Life”: “You’ve had a landscaper and a house keeper since you were born/The starshine always kept you warm.” Can we get Ryan Gosling in the lead?

One might also note a bit of irony in Lalas making such statements. Remember, after a star defensive turn in the 1994 World Cup, the flamboyant long-haired, guitar-strumming ginger signed with Padova of the Serie A. Now if everyone is honest, they will acknowledge that Lalas was never even remotely an elite defensive back, just a really good American athlete who scrapped, fought, and competed really hard. If anything, Padova signed the guitar-slinging jugador (his band the Gypsies put out two albums and even opened for Hootie and the Blowfish in the 1990s) because of his novelty: a prototypical American athlete that could play football in the Italian professional league. Padova signed Lalas because of his nationality, not, at least by international standards, because he was good. Sure, he anchored their defense and scored three goals, but Padova barely survived relegation.

Still, despite any implicit irony, others noted that Lalas’s comments and Twellman’s overly enthusiastic agreement held some merit. Fellow Cultfootball editor Sean Mahoney defended Lalas’s comments to some extent: “A club shouldn’t focus on just one ethnic group to recruit,” he noted, “But his delivery was as deft as you’d expect coming from the likes of him.” After all, soccer, in Europe, Latin American, Africa, and Asia, often comes draped in nationalism and ethnocentrism. Sure, it might be the world’s most popular sport and international football leagues contain some of the most diverse locker rooms around the globe, but it also remains rife with racial and ethnic prejudice. One need only look at reference books like How Soccer Explains the World or witness frightening displays of anti-semitism and racism in European leagues to see how these issues often manifest themselves among fans and players. One does not exaggerate when they claim football matches have sparked civil wars and international conflicts. So the fact MLS seems devoid of these tensions, thus far at least, should be seen as a positive, therefore some could argue Chivas’s policy to be a can of worms the league wants to reseal.

While others have highlighted Chivas’s new direction, some writers have noted the strategy isn’t new. According to blogger and broadcaster Jonathan Yardley, Chivas’s recent front office decisions actually reflect a return to previous incarnations. “[T]hey are basically re-starting the club and returning to its original intent: to be an American version of Chivas Guadalajara, playing a Mexican style and fielding a mix of Mexican-Americans, Mexican players on loan, and Californians,” he noted in a recent post. According to Yardley, rumors abound that all front office staff are expected to know Spanish and Chivas jettisoned English-language broadcasts. Still, though he expressed reservations, Yardley also admitted that if Chivas succeeded in putting a superior or at a minimum a very different style of play on the field, it might increase interest as American (though it remains unclear just what “American style” soccer is) and Mexican approaches to the sport “clash.” Moreover, considering the amount of antipathy between Mexico and America’s national teams – between players themselves and fans – Chivas might serve as a the “heel” of the league. A 2013 version of the Detroit Piston Bad Boys of the 1980s, an effective but hated opponent: “They could be a hated rival for every team with a fan base that loves the U.S. national team.” Then again, one wonders if this might slip into unhealthy jingoism that painted every game as some sort of battle between an invading Chivas’s Mexican “other” and whatever random MLS team they play against. While Mexican immigration has dropped precipitously in recent years, to the extent that Asians have replaced Mexicans as the largest group immigrating to the US, tea partiers, birthers, minutemen, and others continue to blow nativist dog whistles and ring xenophobic bells. Soccer as foreign scourge threatening US values may be a diminishing trope (google “soccer” and “socialism” and see what you get), but it persists. Perhaps, Chivas’s new direction might exacerbate this tension.

Of course, one needs to consider Chivas’s financial situation. Professional sports remains a business and when competing with the L.A. Galaxy – even if devoid of the magically inconsequential David Beckham – drawing fans has proven difficult. Remember, the second largest city in America still doesn’t even have an American football team, having failed to keep both the Rams and Raiders. Only 7,121 fans attended Chivas’s home opener this year; the smallest home opener in league history. Even worse, numerous observers alleged that the real attendance may not have even reached 4,000. Granted, league wide attendance for opening weekend declined by nearly 10% but 4,000 spectators at the Home Depot stadium does not spell success. When one considers that NBC recently fell behind Univision in network television ratings, maybe all-Spanish broadcasts of their games makes more sense. In this way, can anyone blame Chivas for trying to capitalize on the millions of Southern California Latino Americans in the Los Angeles and yes, Orange County area (Latinos make up 1/3 of its population and Asian Americans another 1/4)? In its initial years the MLS played with ethnic affiliations in cities like Chicago, purposely placing Eastern European players on its roster in hopes of drawing more Polish and other Slavic residents to home games. Currently, the national team under Jurgen Klinsman has been openly courting American players of German descent to the point that some simply call them the Von Trapps (see Sound of Music). The aforementioned Davies and Bennett frequently joke about the illegitimate offspring of U.S. G.I.s and Germans as the life blood of American national team hopes. If Chivas’s move is so offensive then why does no one complain about a national team that focuses on its German American descendants?

Some of this has to do with MLS’s audience and the league’s grasp of it. This greatly complicates matters. In late January, Lalas provided some water cooler talk with the following tweet: “You’re not a true American soccer fan if you ignore MLS, you’re part of the problem.” Whatever you think of Lalas’s line in the sand, it gets at a core issue: what does MLS mean to American soccer fans? Mahoney expanded on this, pointing out that while the dominant cultural sport in most of the world, soccer’s popularity in America stemmed in no small part to its outsider status. Being a soccer fan in the US, for a particular segment of the audience, includes an aversion to other American “big time” sports. Less generous observers describe these followers as sort of “sports hipsters,” interested as much in a statement about aesthetics and politics than just sports. “In part, the situation is this sort of ‘hip’ subculture that exists as a group of people who are anti-big American sports (which is really anti-all that goes along with big us sports culture, e.g. big fat sweaty (white) guys who are usually some combination of racist, sexist, homophobic, and xenophobic),” noted Mahoney. Unfortunately for the MLS, most of this demographic prefers La Liga or the EPL to MLS. The key, argued Mahoney, lay in finding a connection between this “’underground cred’” and MLS. However, not everyone sees this as a realistic enterprise. “Manufacturing Cred,” fellow football blogger and CF writer Ron Kirby argued, “So you cultivate credibility, and then kids who abhor stadium commercialization will attend? Better to pair underage booze with underground [football] in illegal nightclubs.”

Competing with European and Mexican league sides places the MLS at a disadvantage. No matter what league officials say, the MLS remains a solid but middling league, perhaps on par or near parity with Mexico’s professionals but still greatly apart from the EPL and many other European associations. Convincing white hipsters, immigrants, and others that MLS has the better product continues to be a dicey proposition. Lalas never said ignore those other leagues, but getting people to fill a Brooklyn pub or San Diego beer hall to catch the latest clash between Real Salt Lake and the Colorado Rapids in the same way they do for national team games, the Euros, World Cup, or even EPL derbies, continues to be one of MLS’ greatest challenges. Grantland founder and editor Bill Simmons frequently highlights the fact that Americans like soccer, but they want to watch it at the highest level, no matter where it happens, rather than what some, perhaps incorrectly, perceive as an inferior MLS product.

If you’re wondering about the league’s racial makeup in terms of players, coaches, and administrators, MLS does quite well regarding gender and race. A November 2012 report by The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sports (TIDES) gave the MLS a B+/A- for “racial hiring practices” an A+ for its diversity initiatives and the multi-ethnic/racial background of its players. It also improved representation in management circles. However, it should be noted, while the league went from a D to a B- regarding general managers, it also dropped to a C+ in terms of head coaching positions. Though the percentage of assistant coaches rose from 18% in 2011 to 19% in 2012, last year, Chivas and Colorado were the only teams led by minority head coaches. In the end, the league improved its overall gender and racial diversity enough to move from an overall B in 2011 to a B+ the following year. Honestly, when one thinks of recent incidents in the EPL – John Terry and Anne Hatheway look alike Luis Suarez – the MLS seems a bastion of tolerance.

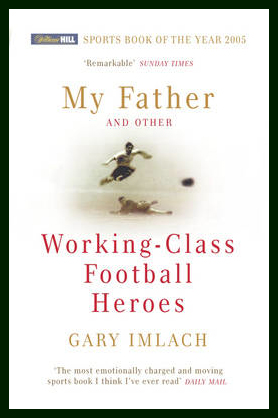

In America, for better or worse, soccer continues to be a largely suburban sport punctuated by white faces. One of the ironies of Twellman and Lalas’s angst is the way in which they ignore the infrastructure that radically favors these players. Sure, suburbs are changing – more Latino, black, and Asian families have put down stakes in suburbia and by extension this infrastructure. However, under 17 tourneys, regional ODP teams, or local club soccer requires time and a parent willing to chauffeur and pay for this development. MLS officials, thus far, are not delving into working class Mexican American enclaves or inner city communities for footballers. No, for American players, the pipeline to the MLS still travels through the land of soccer moms and SUVs. For Lalas and Twellman to pretend otherwise misses the MLS’ far more complicated, if also promising, predicament.