[Editor’s note: This is the 4th installment in the ongoing Dictators and Soccer series. See also the previous installments on Kim Jong-il and North Korea (or Football, Famine and Giant Rabbits), Nicolae Ceaușescu of Romania and Mobutu Sésé Seko of Zaïre. Stay tuned for Col. Gaddafi next.]

Sovereign city state nations with populations less than 1,000 find themselves irresistibly drawn to soccer. Or perhaps that pertains only to one-man rulerships like Vatican City, right smack in Rome, that can’t help but intersect with soccer and watch it blow up in their faces. When soccer runs amok, it self-inflates beyond all suggested parameters and eventually explodes, pressure pumped beyond the limits. (Picture serious, furrowed Vatican eyebrows in 2012, of which more to come.) But after a period of Catholic guilt, soccer redeemed itself when the offbeat priest-and-seminarian Vatican league called the Clericus Cup came to the papacy’s rescue in 2013, relaunched and refrocked from the previous spring’s flat-lining of the tournament. “Rescue” may overstate the case. Puff pieces on the unofficially taglined “Vatican World Cup” may not have substantively changed hearts and minds or effectively deflected scandal from the Vatican, per se, but they did and do provide comic relief, so you have to take that in consideration.

And now we find ourselves with a likeable Argentinian pope and a Saturday, May 18 Clericus Cup final match at the Pontificio Oratorio di San Pietro, in the hills overlooking St. Peter’s Basilica. Vatileaks, who? Sex scandal, what? Once upon a time, however, the future did not look so bright in Vatican City.

And now we find ourselves with a likeable Argentinian pope and a Saturday, May 18 Clericus Cup final match at the Pontificio Oratorio di San Pietro, in the hills overlooking St. Peter’s Basilica. Vatileaks, who? Sex scandal, what? Once upon a time, however, the future did not look so bright in Vatican City.

Pope Benedict XVI, previously known as Joseph Ratzinger, the battle tank Panzerkardinal enforcer of Catholic orthodoxy, “God’s Rottweiler,” abruptly and inexplicably resigned on February 11, 2013, the first living pope to do so in 600 years. The surprise announcement put the Vatican under intense scrutiny. Theories abounded, with topics trending on corruption, cronyism, blackmail, male prostitutes and a clergyman allegedly caught on video chatting it up on a gay dating site. The scandal had set up shop not simply within the Church but within the sacred walls of the Vatican itself.

Unprecedented in its magnitude and wholesale breach of internal security, the scandal had infiltrated the Roman Curia, the elder priest junta that runs the Church. Ratzinger had ridden out the storm when it surfaced that he had joined the Hitler Youth party in 1941 at 14 years old (semi-involuntarily, as the Nazis offered no alternative), but this was another thing altogether. A splinter faction of the curia actively leaked documents to the press in 2012 to undermine the pope and his number two. Meanwhile, high-ranking gay priests allegedly started getting blackmailed by former flings. After the 2012 Vatileaks scandal but before his resignation, Benedict XVI had commissioned three retired cardinals to investigate and report back on their findings regarding the leaks, the attacking faction of the curia and any extracurricular sex scandals involving the curia. In January 2013 the report landed on his desk. On February 11, he announced his resignation.

As all politicians know, it proves handy at times to have a news distraction, even for a semi-untouchable benevolent dictatorship like the papacy in Vatican City, with only 800 residents but a virtual population of 1.2 billion Catholics worldwide. Fortunately, the Clericus Cup kicked off days after the pope’s resignation news, in a well-orchestrated media campaign. Whether convenient or calculated, the men-of-the-cloth-only soccer tournament would return after getting killed off in 2012. Despite a launch to mass fanfare in 2007 by Benedict XVI’s right-hand man, Cardinal Secretary of State Tarcisio Bertone, a Juventus diehard who moonlighted as a soccer radio announcer while Archbishop of Genoa and reprised commentary for some Rome derbies over Vatican radio, the league saw the plug pulled in 2012 for losing sight of its ideals, namely two: not bringing the name of the Church into disrepute and not sabotaging perceived Christian values with questionable tackling, blatant diving and/or thuggery during or between play. PR is a perception game.

As all politicians know, it proves handy at times to have a news distraction, even for a semi-untouchable benevolent dictatorship like the papacy in Vatican City, with only 800 residents but a virtual population of 1.2 billion Catholics worldwide. Fortunately, the Clericus Cup kicked off days after the pope’s resignation news, in a well-orchestrated media campaign. Whether convenient or calculated, the men-of-the-cloth-only soccer tournament would return after getting killed off in 2012. Despite a launch to mass fanfare in 2007 by Benedict XVI’s right-hand man, Cardinal Secretary of State Tarcisio Bertone, a Juventus diehard who moonlighted as a soccer radio announcer while Archbishop of Genoa and reprised commentary for some Rome derbies over Vatican radio, the league saw the plug pulled in 2012 for losing sight of its ideals, namely two: not bringing the name of the Church into disrepute and not sabotaging perceived Christian values with questionable tackling, blatant diving and/or thuggery during or between play. PR is a perception game.

Now, however, the Vatican had brought the Clericus Cup back from the dead, and the Vatican doesn’t just do things off the cuff or on the fly. Why disinter the tournament that had so embarrassed the church with unsportsmanlike priest and student priest behavior the previous spring?

Through the press, anonymous colleagues hammered Cardinal Bertone for months with charges of Machiavellian methods, palace intrigue, curia cronyism and Vatican banking corruption. However, they did it by proxy, the sneakiest means of self-same palace intrigue. The anti-Bertone faction of the curia used letters written by others which then got the full oxygen of publicity through international news outlets.

In a scandal that developed into the phenomenon “Vatileaks,” a militant faction of the curia leaked confidential letters written to Pope Benedict XVI and Cardinal Bertone, many of which stolen directly from the pope’s quarters by his butler. Investigative reporter Gianluigi Nuzzi published them into a powderkeg collection as His Holiness: The Secret Papers of Benedict XVI in May 2012 and all hell broke loose. The documents proved intensely embarrassing and damaging to both Benedict XVI and Bertone, painting a picture of a lax, ineffective pope who over-delegated to a corrupt second in command.

In a scandal that developed into the phenomenon “Vatileaks,” a militant faction of the curia leaked confidential letters written to Pope Benedict XVI and Cardinal Bertone, many of which stolen directly from the pope’s quarters by his butler. Investigative reporter Gianluigi Nuzzi published them into a powderkeg collection as His Holiness: The Secret Papers of Benedict XVI in May 2012 and all hell broke loose. The documents proved intensely embarrassing and damaging to both Benedict XVI and Bertone, painting a picture of a lax, ineffective pope who over-delegated to a corrupt second in command.

The leaked letters also presented underlings learning too late that any time a whistleblower priest stepped forth about financial corruption within the Church, one of Bertone’s people replaced the letter-writing penpal turncoat. Bertone replaced the governor of Vatican City, the head of the Vatican treasury, and the Vatican’s top bank regulator with his chums from the Piedmont area around Turin (where both he and soccer giant Juventus hail). Any financial malfeasance whatsoever in the Vatican means big money—its portfolio and holdings add up to approximately $6 billion—and international financial bodies have begun to consider the in-house bank as a vehicle for money-laundering and tax evasion. At the moment, it’s safe to say the Vatican bank is not the whitest or most fiduciarily trusted lamb in international banking.

Meanwhile, out of not-really left field, a sex scandal involving high-level priests cinched the vise of his actual day job a few notches tighter. And as Benedict XVI make up his mind to fly the coop stage left, it so happened Cardinal Bertone was about to take charge as the acting head of state. In the interregnum between popes, the camerlengo, or chamberlain, takes charge. After Benedict XVI’s resignation, Cardinal Bertone had the winning trifecta ticket of camerlengo, brainchild of the Clericus Cup and epicenter of vicious controversy. Only two of those three claims to fame did he enjoy.

But surely soccer could lighten the mood. In the annual Clericus Cup five-a-side tournament and its spring-weather soccer Saturdays–Sunday matches understandably verboten—international students from Roman seminaries and plucky older priests playing cup soccer makes the soul smile. The teams’ seminary school fans cheer in Latin, the global aspect makes for interesting contrasts in styles, and scripture in shin pads stops just short of qualifying as official uniform, easily the most pervasive match day routine, hands-down. (Perhaps the verses help stave off bruising with the extra padding.) Add to that a Vatican-only blue card that sends players to a hockey-style penalty box called the “sin bin” for 5 minutes of suspension and reflection on one’s misdeeds, and you’ve got a bona fide sports hit on your hands.

But surely soccer could lighten the mood. In the annual Clericus Cup five-a-side tournament and its spring-weather soccer Saturdays–Sunday matches understandably verboten—international students from Roman seminaries and plucky older priests playing cup soccer makes the soul smile. The teams’ seminary school fans cheer in Latin, the global aspect makes for interesting contrasts in styles, and scripture in shin pads stops just short of qualifying as official uniform, easily the most pervasive match day routine, hands-down. (Perhaps the verses help stave off bruising with the extra padding.) Add to that a Vatican-only blue card that sends players to a hockey-style penalty box called the “sin bin” for 5 minutes of suspension and reflection on one’s misdeeds, and you’ve got a bona fide sports hit on your hands.

The league came up with a couple minor additional ground rules. First, no games on Sunday, for reasons the seminarians really shouldn’t need to be told (again). Second, matches would conclude not with players in single file, slapping palms, mumbling, “Good game, good game,” but with the teams praying together on field at the center circle. It definitely didn’t scream scandal material, more like bleach-clean Christian fun.

Judging from highlight clips aplenty on the Web, the player-priests from Brazil, Mexico, the United States, Italy, Africa and beyond have some genuine soccer skills. And devoted fans. During matches, spectators chant team-specific songs in Latin, and draw from a deep well of languages to heckle referees, insinuate bribery, shout for dismissals and hurl abuse at players adjudged to have dived. In short, a student priest with a foam finger announcing himself “Number One Fan” behaves like any other soccer fan (excepting Latin fluency).

Matches last two 30-minute halves–more elder-friendly, less ungodly–and teams have one time out per half. The red card theoretically exists for the unlikely scenario of one of the player’s taking the Lord’s name in vain—reflection on that misdeed in light of one’s career choice clearly requires more than 5 measly minutes. Over 300 international seminary students and priests in Rome represent 50+ countries on Saturday soccer fields just outside of Vatican City (given its size, the country has no dedicated soccer pitch) to celebrate discipline, clean-cut values and the occasional wondergoal. The players pose for photographs as upstanding paragons of Catholicism, with the awe-inspiring cupola of St. Peter’s Basilica in the distance. What could be more wholesome?

Matches last two 30-minute halves–more elder-friendly, less ungodly–and teams have one time out per half. The red card theoretically exists for the unlikely scenario of one of the player’s taking the Lord’s name in vain—reflection on that misdeed in light of one’s career choice clearly requires more than 5 measly minutes. Over 300 international seminary students and priests in Rome represent 50+ countries on Saturday soccer fields just outside of Vatican City (given its size, the country has no dedicated soccer pitch) to celebrate discipline, clean-cut values and the occasional wondergoal. The players pose for photographs as upstanding paragons of Catholicism, with the awe-inspiring cupola of St. Peter’s Basilica in the distance. What could be more wholesome?

When the papal resignation announcement arrived, the PR machine sprang impressively into action. Benedict XVI informed the cardinals of his resignation at the Apostolic Palace on the morning of February 11. On February 15, the Cup’s Facebook page started pumping out photos of the picturesque St. Peter’s Basilica background and posts like the sic-worthy, “Big news are coming soon…. New edition is warmin up!” The Twitter account similarly crackled to life the same day with the again-English heads up: “we are warming up for a new edition… are you READY?” Normally both accounts post predominantly in Italian.

The Guardian got a sneak peek video onto the Web before the official announcement–Wired’s online article and video even coincidentally/perfectly came out on February 11, the same day as the pope’s shock news.

Before that, there had been radio silence for months. Why the sudden turnaround? Right, right. Inquisition rules–they ask the questions around here. The radio-announcing canon law power player Bertone knew full well the power of soccer over the flock. The swarming world press preferred salacious tabloid scoops, but the occasional fuzzy feel-good story would do.

A press conference on February 21 featured Spanish national team coach Vincent Del Bosque sending a light-hearted video shoutout to the Spanish team of the seminary Pontificio Collegio Spagnolo, among other chuckle-inducing PowerPoint pleasantries. The Cup began two days later, four groups of four teams each in World Cup-style group stage format, knockouts begin in the quarterfinals and on to the finish-line Clericus Cup final and pomp of the award ceremony. Thus concludes the seamless rollout.

A week before the UEFA Champions League final between Bayern Munich and Borussia Dortmund at Wembley, the 2013 Clericus Cup final decides a different, more shin-protected victor at the Pontificio Oratorio di San Pietro in those oft-mentioned hills above St. Peter’s Basilica. Before the world learns the European Cup champion, Catholicism crowns the first Vatican World Cup champions of the Franciscan papal era.

On opening weekend, the late February 2013 group stage league games straddled both the first Saturday and Sunday for expediency’s sake, seemingly flouting the Clericus Cup Fight Club Rule #1. Why the special Sunday dispensation? Don’t look for answers from a Vatican press secretary. Strategic silence continues a long tradition for Vatican information givers. Why was the tournament reinstated? The more basic the question, the less it requires direct address from the Vatican HQ. Meanwhile the Vatican perception strike team had leapt into action, executing a laser-focused sequence that activated social media buzz in the week leadup to a press conference that announces the league start two days later, and just 12 since the papal two (or so) weeks’ notice.

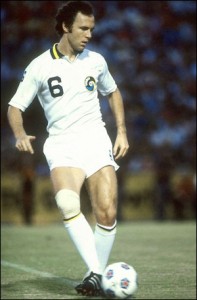

Zooming out for a moment, it helps to revisit the people in charge. Both Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger and Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone served in the 1990s and early 2000s on the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, an office known for such treasured moments in junta history as railroading Galileo into a heresy conviction and shot-calling the Inquisition. Ratzinger presided as top dog prefect and Bertone as the second-in-charge secretary. Heavy hitters in the curia, both priests took part in the 2005 conclave that transformed Ratzinger into Pope Benedict XVI. On Vatican TV, Bertone the wise palace politician invoked the German legend Franz Beckenbauer of Benedict XVI’s favorite team Bayern Munich and obsequiously exclaimed, “The Church has found its Beckenbauer!”

Zooming out for a moment, it helps to revisit the people in charge. Both Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger and Cardinal Tarcisio Bertone served in the 1990s and early 2000s on the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, an office known for such treasured moments in junta history as railroading Galileo into a heresy conviction and shot-calling the Inquisition. Ratzinger presided as top dog prefect and Bertone as the second-in-charge secretary. Heavy hitters in the curia, both priests took part in the 2005 conclave that transformed Ratzinger into Pope Benedict XVI. On Vatican TV, Bertone the wise palace politician invoked the German legend Franz Beckenbauer of Benedict XVI’s favorite team Bayern Munich and obsequiously exclaimed, “The Church has found its Beckenbauer!”

Bertone went further with the Beckenbauer theme, although his descriptions largely fail to evoke the actual attacking defender. “He pushes us forward with his passes. He knows how best to use his teammates’ talents. He is a reserved director and a reliable midfield player.”

For those not familiar with Beckenbauer, or “Der Kaiser,” in addition to his haul of World Cups, the sweeper collected many Bundesliga trophies with Bayern Munich and a disco 1970s late-career segment playing with Pelé in the NASL with the New York Cosmos. Considering other possible German World War leader nicknames, Beckenbauer fortunately ducked “Der Führer.” Fortunate for Ratzinger, as well, he found himself still semi-embroiled with his association with the Hitler Youth during his wide-eyed Bavarian years.

Swiftly after his gushing comparisons to Beckenbauer, Bertone was appointed by Benedict XVI as Vatican Secretary of State, the second-highest office in the country and the religion, perhaps not in that order. Some even tipped the Italian as the next pope. Not bad for a man whose previous most high-profile moment involved him spitting fire and fuming as the Vatican man who went on the attack against Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, decreeing that believers should boycott the book that spread such egregious lies and gross untruths.

Swiftly after his gushing comparisons to Beckenbauer, Bertone was appointed by Benedict XVI as Vatican Secretary of State, the second-highest office in the country and the religion, perhaps not in that order. Some even tipped the Italian as the next pope. Not bad for a man whose previous most high-profile moment involved him spitting fire and fuming as the Vatican man who went on the attack against Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code, decreeing that believers should boycott the book that spread such egregious lies and gross untruths.

He further mined the vein of soccer goodwill when, in announcing the Clericus Cup months before kickoff in December 2006, new Cardinal Secretary of State Bertone boldly speculated that one day the Vatican could put its own team Seria A team together and pit it against the traditional powerhouses. “The Vatican could, in future, field a team that plays at the top level, with Roma, Internazionale, Genoa and Sampdoria. We can recruit lads from the seminaries. I remember that in the World Cup of 1990 there were 42 players among the teams who made it to the finals who came from Salesian training centers all over the world. If we just take the Brazilian students from our Pontifical universities we could have a magnificent squad.”

Hours of press scoffing later, Bertone chimed in again, clarified he’d been joking and said, “I’ve got much more to do than cultivating a football squad for the Vatican.” The humor of a Catholic youth education based on the Salesian Order had confounded the journalistic laity once again. “It was fantasy fun to spread some cheer and maybe fill a half a page of the newspapers,” Bertone said.

When God’s Rottweiler’s sidekick Cardinal Bertone birthed the soccer oddity known as the Clericus Cup in 2007, it came on the heels of his lifelong club Juventus’ relegation to Serie B after the infamous 2006 Calciopoli match fixing scandal, as well as the infamous headbutt by Zinedine Zidane on Marco Materazzi in the 2006 World Cup final, about which Materazzi later copped to goading Zidane with, “I prefer the whore that is your sister.” Italy won that World Cup but Italian football was in disarray. Bertone proposed a better, cleaner model, a seminary league that would exhibit Christian values on the pitch, lead by example.

When God’s Rottweiler’s sidekick Cardinal Bertone birthed the soccer oddity known as the Clericus Cup in 2007, it came on the heels of his lifelong club Juventus’ relegation to Serie B after the infamous 2006 Calciopoli match fixing scandal, as well as the infamous headbutt by Zinedine Zidane on Marco Materazzi in the 2006 World Cup final, about which Materazzi later copped to goading Zidane with, “I prefer the whore that is your sister.” Italy won that World Cup but Italian football was in disarray. Bertone proposed a better, cleaner model, a seminary league that would exhibit Christian values on the pitch, lead by example.

Then, of course, it had to shut down in 2012 for misconduct and corruption of the original purpose. But nothing substantively had changed. The competition had had scuffles, referee abuse and noise complaints from neighbors about the drums, music and overall decibel level since the beginning.

Whatever the reason, the Clericus Cup got canned. Perhaps it served as the stray dog that wandered into the wrong place at the wrong time, and Bertone engaged in the animal-kicking cardinal equivalent of ripping all the books, pictures and fixtures from the walls in a destructo-tantrum.

Soccer had done what soccer always does in a tightly controlled state of junta or one-man rule. Passions pitched beyond acceptable bounds, the volatile compound exploded, and shrapnel strafed the faces pushing into the publicity shots. It was minimal, but a last straw is a last straw.

It all went swimmingly until got it in their head that the competition was bringing scandal to the church (slight misidentification of the primary target on that one). Reports of unsportsmanlike behavior emerged. Problems had resided in the Clericus Cup from the beginning, however. Nothing about the proceedings in 2012 particularly spoiled the show, but authorities felt aggrieved.

Designed to contrast the match-fixing-embroiled Italian Serie A with a celestially approved alternative, the Clericus Cup prided itself on fair play and the integrity of its players. The organizers selected for its motto, “a different soccer is possible,” and while sometime, somewhere that may be true, the Clericus Cup did not best exemplify that case. News of a pitch brawl spread in 2010, in addition to various Italian press reports of uncharitable chants against rival teams. In the first year, even, contentious calls led to adrenaline-fueled eruptions against the referee, as between Redemptoris Mater and the Pontifical Lateran University in 2007. A questionable penalty elicited protest, chants and a hail of abuse from the crowd. At the final whistle, field indiscipline progressed to off-field antics. The Neocatechumenals of Redemptoris Mater ran to the touchline to rejoice with their fans, which soon escalated into showers of uncorked champagne. Redemptoris Mater, in any crusty priest’s eyes, could have exercised a bit more prudence and moderation in jubilation.

However, in 2012 the main bugaboo for Bertone was Vatileaks, the albatross he couldn’t shake. The Clericus Cup was not top of mind. There was a darker stain on Vatican City than players arguing on the fields. Then suddenly things got worse. His powerful backer resigned. In the fallout from the leaked letters to the pope and the Cardinal Bertone, authorities arrested the pope’s butler and ejected the Vatican bank president for negligence. Pope Benedict later pardoned his butler in December 2012, in what would prove one of his final acts, although no one knew it at the time.

However, in 2012 the main bugaboo for Bertone was Vatileaks, the albatross he couldn’t shake. The Clericus Cup was not top of mind. There was a darker stain on Vatican City than players arguing on the fields. Then suddenly things got worse. His powerful backer resigned. In the fallout from the leaked letters to the pope and the Cardinal Bertone, authorities arrested the pope’s butler and ejected the Vatican bank president for negligence. Pope Benedict later pardoned his butler in December 2012, in what would prove one of his final acts, although no one knew it at the time.

In the fallout, Cardinal Bertone accused journalists of “pretending to be Dan Brown” and channeling the sensationalism of the author’s The Da Vinci Code, ascribing to the profession “a will to create division that comes from the devil.” One wonders why he didn’t just go on an excommunication spree, aside from the Clericus Cup whose primary fault was aligning in time with the prepublication hype of His Holiness: The Secret Papers of Benedict XVI.

Regardless of punished parties, Cardinal Bertone’s reputation took a massive hit. The Italian media skewered Bertone, though Pope Benedict XVI came to his defense in a July 4 letter, subsequently released as a statement by the Vatican. Benedict XVI inclusively called Bertone “dear brother” and thumbs-upped the continued co-sign with, “Having noted with sorrow the unjust criticisms that have been directed against you, I wish to reiterate the expression of my personal confidence.”

In January, after the detective cardinals wrote up the dirt for Benedict XVI, the pope decided not to share the findings with the cardinals entering the conclave, that only the next pope would be shown the dossier. Did Bertone read it? Unknown, but it’s reasonable to assume that unless he featured prominently, Benedict XVI handed it over to him within minutes of reading, before or after asking for some painkillers and a place to lie down. Bertone may have even read it first, in accordance with criticism of Benedict XVI’s hands-off administrative posture, to detractors’ minds the root of the problem.

Even before the pope drafted the three cardinals for CIA op cloak and dagger action, Bertone had set into motion his own investigations. According Italian magazine Panorama, he instructed the head of the Vatican police to tap the phones and monitor the emails of selected curia cardinals and bishops, prime suspects in his dissident roundup. According to a spokesman, someone or someone’s “authorized some wiretaps or some checks.” Simple as that. Just a minor experiment in police state surveillance for more transparency in information flow patterns. Bertone wanted to catch the bastards that burned him with the Vatileaks and the book.

By the time Pope Benedict XVI did his last papal rites on February 28, Bertone had already set into motion the Clericus Cup campaign. On March 1, he transitioned into acting head of state–the official title for the job description he had essentially held all along. The first weekend of Bertone’s interim regime, the Clericus teams generated positive news through respectful inaction, observing the departure of outgoing Benedict XVI with a day of soccer field silence. Before that point, though, they’d granted many smiley interviews and people had stocked up YouTube with the clips. By the time Cardinal Bertone and the rest of the cardinals dipped into the conclave, the teams entered into the last final clutch matches of the group stages, but bantered easily again with eager reporters asking softball questions about who they were rooting for when it came to the next pope. (Brazilians: “A Brazilian!” The Argentines: “An Argentine!” Africans: “An African!”) Hard hitting journalism it was not.

The conclave sent up the white smoke on March 13, and Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina emerged from the St. Peter’s Basilica balcony as Pope Francis I. In the next batch of Clericus Cup YouTube videos, the Argentines of Incarnate Word seminary team in particular cheered, in vergingly overexuberant fashion, the selection. Reinstated after getting so unceremoniously defrocked, the Clericus Cup returned with the renewed life force of a Lazarus. Reporters canvassed players during the conclave, some of the best press to come out of the Vatican in year s.

s.

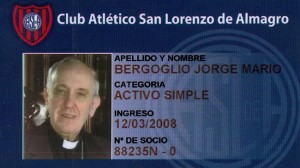

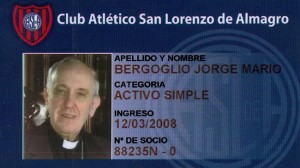

Before presiding as the archbishop of Buenos Aires, Bergoglio grew up a fan of Buenos Aires side San Lorenzo de Almagro, or “Los Santos” (the Saints). The Saint’s Twitter account reacted to the pope’s announcement with respectable speed. Within hours of Pope Francis’ succession to the papal throne, a scanned membership card with his picture, name and number flew over airwaves. The new pope literally qualified as a card-carrying fan.

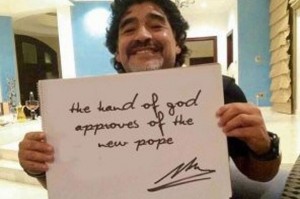

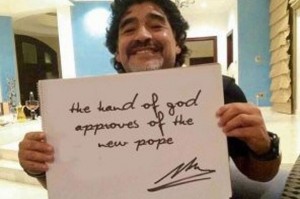

Also in the first few hours and also tweeted, a photo of Diego Maradona, grinning while holding a handwritten “The hand of God approves of the new pope.” El Diego later followed up with the media proper. “The god of soccer is Argentine,” Maradona humbly opined. “And now the pope is too.”

Pope Francis I comes across as a good guy, a likeable and as-yet-uncompromised papal figure. Nevertheless, his handlers must urge caution with soccer. To wit, action one: prioritize. Keep the Clericus Cup, ditch Bertone at the first opportunity. (Francis I convened an advisory council with regard to the Secretary of State office in March, but the sooner someone new walks in, the sooner things die down over the Vatileaks incident, the more people read mood relaxers about Vatican football/soccer/futsal, the better. It’s the Catholic Church–what are they going to do? Change?) Action two: unleash a FIFA national team that challenges for world honors, with a merry band of Swiss Guards bossing the upcoming 2018 Russian and/or 2002 Qatari World Cup grounds. But that’s a discussion for another time.

Pope Francis I comes across as a good guy, a likeable and as-yet-uncompromised papal figure. Nevertheless, his handlers must urge caution with soccer. To wit, action one: prioritize. Keep the Clericus Cup, ditch Bertone at the first opportunity. (Francis I convened an advisory council with regard to the Secretary of State office in March, but the sooner someone new walks in, the sooner things die down over the Vatileaks incident, the more people read mood relaxers about Vatican football/soccer/futsal, the better. It’s the Catholic Church–what are they going to do? Change?) Action two: unleash a FIFA national team that challenges for world honors, with a merry band of Swiss Guards bossing the upcoming 2018 Russian and/or 2002 Qatari World Cup grounds. But that’s a discussion for another time.

On April 13, with the Vatican riding high on the positive reception to a well-liked pope, the quarterfinals signaled the knockout phase of the tournament. Team knocked out team and now the finals go down tomorrow. Tomorrow, May 18th, it’s the Vatican World Cup finals featuring reigning champions Pontificio North American College, the “Martyrs,” Maria Mater Ecclesiae and the small matter of the Clericus Cup title. And to warm up the crowd for the main event, the battle for bronze between third and fourth (a.k.a., the semifinal losers).

The Martyrs booked the first final spot by edging past Pontificio Collegio Urbano 1-0, whose supporters, incidentally, drape themselves in Vatican City flags. That is, when they’re not manically waving them (it’s their schtick). And then, in the next match on the same ground–the ultimate in the Catholic World Cup doubleheaders—Mexican side Maria Mater Ecclesiae gunned down Redemptoris Mater, the most winningest team in the history of the Clericus Cup, with a solid 2-0 scoreline.

Like the increasingly unrepresentative name “The Martyrs,” the North American seminary can’t honestly claim the plucky-American-soccer tag, since they have an English ringer on the squad that played semi professionally and once belonged to the Blackburn Rovers youth academy, now to a New York diocese. Another squad player is an Aussie.) In five a side, one ringer goes a long way. Perhaps they could change their nickname to something like “The Masked Crusaders” in line with a fan base that demonstrates deep costume wardrobes. Spectators frequently include superheroes like Captain America, Spiderman or Wolverine, the occasional Ninja Turtle, pirate or, in the case of the semifinal match, a giant chicken. Given the level of creativity in their support, one expected more inspiration in the team call sign, “Stars and Stripes,” but to each their own. With both an Englishman and an Australian on the team, whose national flags superimposed have stars and stripes, perhaps a mediator thought it the most team-bonding option.

Maria Mater Ecclesiae clearly have the Madonna on their side, the seminary having explicitly name-checked her with the school name “Mary, Mother of the Church.” And if Christian hype tales of Mary’s beatitude carry any merit, she surely locks down odds-on-favorite for the best bet.

The Martyrs hope to retain the soccer hat in their winner-take-all against Maria Mater Ecclesiae. In the past, Pope Benedict XVI touched a copy of the trophy, albeit as a ceremonial present he probably had sent off to the furthest treasure lots on the premises. Pope Francis I, should he be not find himself on other more pressing papal business, seems like he’d be up to kick it up a level and present the trophy himself. He may even ask for one of the players’ jerseys. (A Jesuit by trade and humble by disposition, Francis has in his short reign racked up an impressive soccer jersey collection. A Spain national jersey signed by all the players, hand-delivered signed jerseys from Lionel Messi and Javier Zanetti, a team-signed jersey from his lifelong club San Lorenzo and even recently another San Lorenzo jersey from someone in the crowd as he drove through St. Peter’s Square.)

The Martyrs hope to retain the soccer hat in their winner-take-all against Maria Mater Ecclesiae. In the past, Pope Benedict XVI touched a copy of the trophy, albeit as a ceremonial present he probably had sent off to the furthest treasure lots on the premises. Pope Francis I, should he be not find himself on other more pressing papal business, seems like he’d be up to kick it up a level and present the trophy himself. He may even ask for one of the players’ jerseys. (A Jesuit by trade and humble by disposition, Francis has in his short reign racked up an impressive soccer jersey collection. A Spain national jersey signed by all the players, hand-delivered signed jerseys from Lionel Messi and Javier Zanetti, a team-signed jersey from his lifelong club San Lorenzo and even recently another San Lorenzo jersey from someone in the crowd as he drove through St. Peter’s Square.)

Benedict XVI has a replica of the silver soccer priest man silverware, as does Cardinal Bertone. To see the Saturno is to gaze upon the purest in bizarre Catholic-commissioned artwork. The unique specimen sports a giant silver disc of a Vatican flat hat atop a legless soccer ball nestled on a pair cleats, like a metallic, spherical pygmy priest that leaves waddling, spectral, studded footprints. With an extra-wide circular brim like the rings of Saturn, this specimen of soccer trophy awaits the lucky winner that prevails from February to May and takes top honors.

Benedict XVI has a replica of the silver soccer priest man silverware, as does Cardinal Bertone. To see the Saturno is to gaze upon the purest in bizarre Catholic-commissioned artwork. The unique specimen sports a giant silver disc of a Vatican flat hat atop a legless soccer ball nestled on a pair cleats, like a metallic, spherical pygmy priest that leaves waddling, spectral, studded footprints. With an extra-wide circular brim like the rings of Saturn, this specimen of soccer trophy awaits the lucky winner that prevails from February to May and takes top honors.

Before its death and rebirth, the Clericus Cup roared onto the scene in a blaze of glory. For a quick six-season primer, the inaugural title in 2007 went to Redemptoris Mater, who defeated the Pontifical Lateran University. Redemptoris Mater played in the tournament’s first four championship finals, winning three. Then, taking the mantle, the Pontifical North American College, the self-styled Martyrs, came into ascendance, losing two finals and two semifinals before finally lifting the odd silver trophy in 2012 against a team that had a bona fide cardinal in its ranks (albeit on the bench, to support the aforementioned Aussie), the Australian Gorge Pell. The Martyrs looked forward to defending their crown.

But in 2012 the Vatican cited failure to fulfill the sworn aim of educating young people about fair play and sportsmanship and withdrew its support. What had been conceived as a living model of the fostering of peace, honor and morality through sport had gone horribly wrong. The Clericus Cup had to pack up and shut down operations, effective immediately. Permission withdrawn, readmission denied. The Martyrs would not get the opportunity to defend their title.

We skip back and forth in time, but fast forward again to 2013 and the tournament’s reprieve. The powers that be rescinded the previous rescinding and the league kicked off again in February, back on that picturesque hillside overlooking St. Peter’s Basilica. Anyhow, just like a secretary of state may on occasion wear his minister of propaganda hat, abracadabra, alakazam, and the league materialized just in time to semi-deflect attention from Benedict XVI resignation news. Whether Bertone is a white hat or a black hat, he surely played his part in the mini-distraction that goes by the nickname of the Vatican World Cup.

The hunt for the Martyrs was back on. Is back on. As for first-time hopeful Mater Ecclesiae. The last stretch remains, but will be settled by mass on Sunday. Hunt in packs and take top prize, or roll over like a conscientious objector. WWBD? What would Bertone do?

He certainly wouldn’t conscientiously object. He’d set up a tournament and craft a compelling narrative. He’d hook the public with a high-definition soccer display. And then he’d make a bid for world domination.

Dictators and Soccer/Football:

Mobutu Sésé Seko (Zaïre)

Nicolae Ceaușescu (Romania)

Kim Jong-il (North Korea)

Pope Benedict XVI (Vatican City)

https://twitter.com/tyrannosoccer

https://www.facebook.com/DictatorsAndSoccer

Copyright © 2013

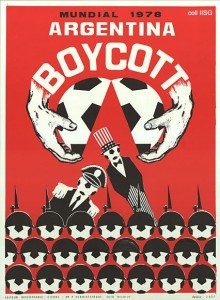

The generals had a three-point plan. Silence all dissent. Grease the wheels to first prize. Claim the glory as their own, a divine right along with the total subjugation of the people in their reign of terror. But the people would wear smiles for the cameras. Never mind that between 1976 and 1983 the junta brought about the death of 30,000 fellow Argentines. Or that as in Pinochet’s Chile, soccer stadiums sometimes doubled as temporary detention centers for political prisoners. One can understand why the world community might have issues with a World Cup in late-’70s Argentina.

The generals had a three-point plan. Silence all dissent. Grease the wheels to first prize. Claim the glory as their own, a divine right along with the total subjugation of the people in their reign of terror. But the people would wear smiles for the cameras. Never mind that between 1976 and 1983 the junta brought about the death of 30,000 fellow Argentines. Or that as in Pinochet’s Chile, soccer stadiums sometimes doubled as temporary detention centers for political prisoners. One can understand why the world community might have issues with a World Cup in late-’70s Argentina.

Ironically, considering Maradona’s later infamous drug busts, some players may also have been given illegal injections for the match. Insiders say Mario Kempes and Alberto Tarantini had to keep running after the match to wear off the excess effects and that a waterboy had to provide urine samples.

Ironically, considering Maradona’s later infamous drug busts, some players may also have been given illegal injections for the match. Insiders say Mario Kempes and Alberto Tarantini had to keep running after the match to wear off the excess effects and that a waterboy had to provide urine samples.

![[soccer1204]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-QW036_soccer_D_20111204121118.jpg)