[Editor’s note: We welcome back contributing writer and longtime friend Ryan Reft. He’s kindly allowed us to repost this essay from his groupblog Tropics of Meta. For some of his past contributions to CultFootball see here, here and here.]

Over the past fifteen to twenty years, historians have increasingly emphasized the role of sports as both a driver and reflection of society. The recent Bill Simmons-inspired and ESPN-produced 30 for 30 documentary series tackled a number of difficult subjects via sport. In “The Two Escobars“, directors Jeff and Michael Zimbalist travelled through 1980s Columbia, following the lives of Pablo (international drug dealer/murder/local philanthropist) and Andres Escobar (captain of Columbia’s 1994 World Cup team murdered in a nightclub alteration several months later). The two unrelated protagonists encapsulated the travails of late 20th century Columbia. Drug money filtered into the nation’s soccer infrastructure, boosting its competitive success but also adding layers of complexity and violence to a nation already struggling with decades of conflict. Writing for the Onion’s AV Club, Todd VanDerWerff summarized its importance similarly: “The film’s portrayal of Colombia as a nation that made its compromises and learned to live with the hell they unleashed is also particularly good, as the story of the two men at the center slowly radiates outward to encompass more and more of the nation’s society.”

This is not a wholly unusual conclusion for the series. In “Pony Exce$$,” director Thaddeus Matula explored the corruption and ultimate destruction of Southern Methodist University’s (SMU) then dominant football program as booster money flowed in from the oil wealth that defined the Southwest US in the 1980s. Though the Southwestern Conference consisted of eight schools (Baylor, Rice, SMU, Texas, Texas Tech, Texas A&M, Arkansas, and Texas Christian University), Dallas served as a hub for numerous successful graduates of each school. As several observers note in the documentary, football rivalries crackled in the board room meetings of Dallas high rises as alumni from all schools engaged in recruiting practices that seemed to define the decade.

Likewise, Billy Corben’s film,“The U” about the dominance and bravado of Miami University’s 1980s football teams reflects similar themes. Miami’s football team served to unite a divided city behind a collection of local talent that also rewrote the rules of the game. Miami’s players excelled spectacularly on the field but stoked controversy with their trash talk and exuberance. If oil money shaped SMU, Miami’s notoriously tough African American neighborhoods, embraced by Miami’s first successful coach Howard Schnellenberger, came to symbolize “The U’s” power. Along with cultural productions like Scarface, Miami Vice and the notorious Two Live Crew, players like Michael Irvin challenged college football and its fans. Unlike “Pony Exce$$”, “The U” reveals the racial undertones that marked some of the criticism faced by the Miami program. When teamed with Steve James’ masterful “No Crossover: The Trial of Allen Iverson” and the recent “Fab Five” film about the innovative early 1990s Michigan basketball team, “The U” reveals so much more about American life than just college football. Race, money, and a changing cultural landscape collided. As one writer observed, James’ movie looks at Allen Iverson “more as a phenomenon, a human inkblot whose polarizing effect on people often says more about them than it does about him. They see whatever they want to see, and that may or may not be the truth.” In essence, all these films and others in the 30 for 30 series function to elevate sports to a level of political and social importance that might have been derided in early decades.

“Architecture is the simplest means of articulating time and pace of modulating reality and engendering dreams. It is a matter of not only of plastic articulation and modulation expressing an ephemeral beauty, but of a modulation of producing influences in accordance with the eternal spectrum of human desires and the progress in fulfilling them. The architecture of tomorrow will be a means of modifying present conceptions of time and pace. It will be both a means of knowledge and a means of action.” – Ivan Chtcheglov, Forumulary for a New Urbanism, 1953

Writing in 1953, nineteen year old architect and devotee of the Situationist movement, Ivan Chtcheglov published his sweeping indictment of mid-century urban planning. For Chtcheglov, the architecture of cities past reflected the dead life of capitalist production. City dwellers had been hypnotized by the built environment, thus, focusing exclusively on capitalist accumulation to the extent that when “presented with the alternative of love or a garbage disposal unit, young people of all countries have chosen the garbage disposal.” One can see parallels with sport, most clearly in the above examples regarding SMU and the Escobars. The excess capital of drug and oil money created a vehicle for the egos and dreams of ruling classes that were then imposed. (To be fair, soccer teams as several interviewees in The Two Escobar note, serve as great money laundering devices. One might suggest the same of Enron and other corporate entities in recent years.)

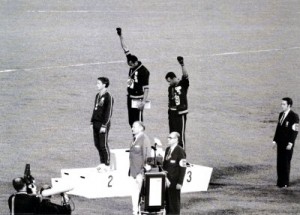

For Americans, sports provided both meaningless entertainment and incredible important cultural moments of resistance. Dave Zirin documents athlete resistance of the twentieth century in his 2005 work, What’s My Name, Fool? Sports and Resistance in the United States. To Zirin’s credit, What’s My Name, Fool? gathers countless examples of political acts by athletes across the sports spectrum, engaging in issues of race, gender, and class. For example, Zirin traces the complicated politics of Jackie Robinson who, despite his bravery in desegregating MLB, came to be unfairly seen by radical Black nationalists of the late 1960s as a sell out. Some have described Zirin as sort of Howard Zinn of spors journalism. Perhaps. He does look at major historical events like the 1968 Mexico City Olympic protest by Tommy Smith and John Carlos, in which both athletes upheld closed black gloved fists. Zirin explores many facets of the event that had gone unnoticed. Unfortunately, while Zirin collects valuable stories worth reflection, he too often veers in the direction of soap box oratory. Moreover, Zirin seems to feel the need to conclude paragraphs with zingers. For example, how about this gem regarding the failure of several WNBA sports franchises: “while some franchises found success, others have folded faster than a rib joint in Tel Aviv.” (186) When discussing Allen Iverson, Zirin notes Iverson’s role as an anti-corporate anti-hero summarizing his nickname may have been A.I. but “there was nothing artificial about him.” (163) Nuance is not the most prominent feature of What’s My Name, Fool. Still, even if the equivalent of street corner radical, Zirin contributes something to our knowledge of American culture and sport.

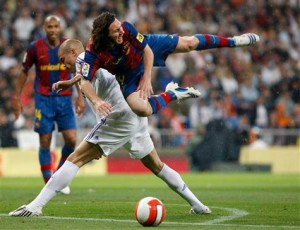

If baseball and to a lesser extent American football and basketball have served as venues for political expression, predictably, football occupies a similar position for Europeans. In How Soccer Explains the World: An Unlikely Theory of Globalization, Franklin Foer traipses through countries around the world, but predominantly Europe, exploring the meanings and processes that manifest themselves in the sport. Throughout How Soccer Explains the World one thing becomes clear, the political complexity of football and more generally, sport, radiates in countless directions. When Foer presents Barcelona’s “bourgeois nationalism” as a model for 21st century cosmopolitanism, he goes so far as to claim that it “redeems the concept of nationalism.” (198) For Foer, Barca never demonizes opponents the way supporters at Red Star (Belgrade- the subject of a previous chapter, one that found soccer fan bases and clubs of the former Yugoslavia as germs for the paramilitary organizations of the Balkan wars in the 1990s) have. Instead, Barca illustrates that “fans can love a club and a country with passion and without turning into a thug or terrorist.” (197)

A central aspect of Barca’s identity rests on its foundational myth, its role as a means of Catalan resistance toward the post Spanish Civil War fascist Franco regime. According to this myth, Camp Nou, Barca’s legendary stadium, enabled Catalan fans to express themselves in ways forbidden by Franco. Camp Nou allowed for political and social subversiveness. “Its fans like to brag that their stadium gave them a space to vent their outrage against the regime,” writes Foer. “Emboldened by 100,000 people chanting in unison, safety in numbers, fans seized the opportunity to scream things that could never be said, even furtively, on the street or in the café.” (204) Yet, as Foer acknowledges, there is another way to view Barca’s history. More likely, Franco saw Camp Nou and Barca as harmless outlets for his repressed populations. Unlike the Basque region and its terrorist/separatist movement ETA, Catalonia never developed any similar liberation fronts.

Instead, Catalans pragmatically went to work, benefiting from subsidies and tariffs that contributed to Barcelona’s metropolitan industrial boom. This success may go far in explaining Barca’s place in the Catalonian psyche. Foer argues, many Catalonians have a self conscious suspicion, that unlike their forefathers and other Spanish regions, “they feel as if they have lived lives devoid of struggle and without epic dimension. They worry that their fathers would be disappointed with their staid existence.” (214) Catalans employ Barca as a “balm” for a guilty conscience and resentments over “Castilian centralism.” Even in this less than ideal motivation, Foer finds strength. Catalans hold contempt for a concept (Castilian centralism” as represented by arch rival Real Madrid) rather than a people, hence the reason Barca lacks the kind of history of hooliganism or violence that seems so prevalent at other clubs. If anything, the history, identity, and place of the Barca (this year’s Champion’s League victor) in Spain points to a deep complexity that lay at the heart of sport in the West.However, one needs to ask, what does sport mean outside the West?

Decolonizing Cricket

“It is no exaggeration to suggest that cricket came closer than any other public form to distilling, constituting and communicating the values of the Victorian upper classes in England to English gentlemen as part of their embodied practices and to others as a means for apprehending the class codes of the period.” (Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimension of Globalization, 91)

“Rock star” anthropologist (probably the equivalent of “rock star bands” like the Soft Pack—what never heard of them? Exactly) Arjun Appadurai also believes sport reveals deeper issues than won loss records. In Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization, Arjun devotes an entire chapter to the “decolonization of Indian cricket.” Appadurai’s interest lay in what he labels the “indigenization” of cricket on the subcontinent. The former University of Chicago anthropologist (he’s currently at NYU) identifies four processes that interacted in ways that led to cricket’s unique indigenization in India:

1) the “implicitly corrosive” affect the “elite Victorian values” embedded into the sport on the “bonds of empire”

2) internal sustainability of the cricket due to its ability to develop talent outside urban

3) issues of post colonial masculinity in which spectating came to be associated with “bodily competition and virile nationalism”

4) the ability of media and language to disconnect Englishness from the sport

Perhaps the most intriguing of Appadurai’s processes is the paradoxical affect that the initial values of the sport exerted. “Quintessentially, masculine”, the codes of cricket regulated broader male behavior. These codes consisted of four essential tenets: 1) sportsmanship 2) fair play 3) emotional control over one’s person 4) loyalty to team and sublimation of personal interests to the group. Yes, it functioned to socialize and discipline subjects, but it also provided an “an instrument of elite formation.” As Appadurai points out, “it both confirmed and created sporting solidarities that transcended class.” (92) The field allowed lower and middle class competitors a limited equality with their Victorian superiors. Appadurai also credits the lower classes with doing “the dirty subaltern work of winning so that their class superiors could preserve the illusion of gentlemanly non competitive sport.” (92) The greater importance, he argues, is that as an elite sport, cricket nonetheless emphasized an idea of fair play that demanded “openness to talent and vocation in those of humble origins … a key to the early history of cricket in India.” (92) English officials believed it to be the perfect way to “socialize natives into new modes of intergroup conduct and new standards of public behavior.” (93)

With that said, one of the most critical developments unfolded as Indian princes began paying English and Australian professional players to train their own squads in India. This line of patronage and the coaching it brought with it proved critical to the sport’s development. Princes loved cricket because it confirmed their own masculinity, provided avenues for furthering their English contacts, and enabled them to extend their places in “royal public spectacles” seen as integral to the intrigue and responsibilities of Indian royalty. This resulted in a class of players form outside India’s major colonial cities. The monies given to them by these Princes allowed for many to occupy a space in the cosmopolitan world of cricket. As these new class configurations compiled, Indian cricket exhibited a class complexity that Appadurai argues “persists to today.” (95) “In the circulation of princes, coaches, viceroys, college principals, and players of humble origin between India, England, and Australis,” writes Appadurai, “a complex imperial class regime was formed.” Functioning as a sort of network of Indian and English “social hierarchies”, by the 1930s the various interactions occurring within this nexus of empire had created a “cadre” of non elite Indians who identified as both legitimate cricketeers and “genuinely Indian.” (96)

Unlike in England, where cricketing organization represented territory and nationhood, Indian organization refracted this meaning instead focusing on community and cultural distinctiveness. This meant Indian clubs were organized around local religious identities. Thus, spectators and players developed distinct ideas about their identities as Hindus, Muslims, and Parsi through the public spaces of cricket. When contests between English sides and those of indigenous colonial players expanded, the idea of India had to be invented. In other words, in order to field a team to play British sides, there existed a need to construct a team that represented Britain’s South Asian possession, India. At the very least, the teams constructed embodied protonational visions of an Indian state. In the post 1948 world, cricket as a vehicle for Indian nationalism seems obvious. Moreover it ties the tangled ends of empire together servings as a space for Indians, Pakistanis, Australians, English, their respective Anglo colonial counterparts, to engage and interact. While Appadurai also notes what he sees as the negative influence of globalized financial flows and commodization, he nonetheless recognizes its powerful undercurrents. “[Cricket] is an agonistic reality, in which a variety of pathologies (and dreams) are played out on the landscape of common colonial heritage. No more an instrument for socializing black and brown men into public etiquette of empire, it is now an instrument for mobilizing national sentiment in the service of transnational spectacles and commoditization.” (109)

Operation Iraqi Freedom

“Iraq as a team does not want Mr. Bush to use us for the presidential campaign,” [Iraqi midfielder Salih] Sadir told SI.com through a translator, speaking calmly and directly. “He can find another way to advertise himself.”

— Grant Wahl, Sports Illustrated, “Unwilling Participants” August 4, 2004

Appadurai’s exploration of cricket through the tentacles of imperialism points to the multivalent nature of sport. Though employed as a means to inculcate imperial pride and English Victorian values, cricket served to sculpt communal identities while contributing to post colonial imaginaries that envisioned an independent subcontinent. With the rise of an increasingly globalized mass media, cricket provided the state with cost free way of emphasizing nationalist tropes to a transnational diaspora.

While American occupation of Iraq differs in many ways from the English equivalent a near century before, many Iraqis view it as neocolonialism. Take, for example, George W. Bush’s attempt to appropriate the newly reconstituted Iraqi soccer team for electoral gain. Linking the team’s achievements at the 2004 Olympics (they ultimately took fourth, a remarkable achievement for a nation at war) with those of his administration, Bush attempted to use it as evidence of his administration’s efficacy. On the eve of the 2004 election, in speeches and ads, Bush lauded the fact that had the US not intervened, Iraq would not have fielded such a successful team. “It wouldn’t have been free if the United States had not acted.” While all players acknowledged that none wanted a return to the days when Uday Hussein tortured Iraqi athletes, neither did they appreciate Bush’s line of logic. Coach Adnan Hamad summed up the general tenor of the team’s opposition: “My problems are not with the American people . . . They are with what America has done in Iraq: destroy everything. The American army has killed so many people in Iraq. What is freedom when I go to the [national] stadium and there are shootings on the road?” Of course, the attempt by an American president to take credit for Iraq’s soccer exploits is ironic for several reasons. Unfortunately for Iraqi players, more than a few observers will conclude American intervention did improve their team’s chances. After all, its fourth place finish remains its highest Olympic finish in soccer. In this way, soccer performs a contradictory function to at once provide a unifying expression of Iraqi identity, one couched in resistance to US prerogatives, while also serving as measure of justification for the very occupation they resent.

Iranian Revolution

Perhaps few places in the world today represent the political power of sport more than Iran. Again, this power flows simultaneously in two directions. Two recent events help convey the duality of soccer. The recent death of Iranian goalkeeper Nasser Hejazi underscores its disruptive effect on the Persian nation’s coercive government. Known as the Eagle of Asia, by most accounts, Hejazi was considered the greatest Iranian goalkeeper in history. Yet, the regime refused to celebrate him, nor did he celebrate it. Banned from national competition due to an arbitrary age limitation placed on the national team by the newly triumphant regime in 1979, Hejazi remained a thorn in the government’s side from then on. In 2004, Hejazi attempted to run for office but was denied by authorities. He later commented on the Iranian government’s failed promises. “I am agonised,” he said, “to see [the authorities] interpret poverty as contentment, inefficiency as patience and, with a smile on their faces, they call this very stupidity wisdom.” (Economist, June 2, 2011) The remark earned him a temporary ban from Iranian television. Even in death, the Iranian government remained fearful. The first half of his funeral drew over 20,000 mourners. As the Economist noted, the chanting of anti-government slogans pervaded the event and authorities quickly whisked the body away to a secret burial where contrary to tradition, no prayers were uttered.

Hejazi complicated football for Iranian rulers. The government had hoped to use the Iranian national team for its own purposes. The 1998 World Cup victory over America provided one such opportunity. However, an unexpected victory over Australia the year before sparked controversy within the regime as Iranians bounded into the streets in celebration. Of course, this being Iran, gender comingling remains distinctly discouraged. One particular English periodical commented sarcastically: “In their delight, men and women surged onto the streets of Iran’s cities and—O tempora! O mores!—celebrated together uninhibitedly.” When the Iranian team lost to Bahrain in 2001, the team played lethargically or as some argued “inertly.” Many Iranians suspected the team had been bribed or threatened by the powers that be. Hejazi had long advocated women attending games with men, and the fact that women attended his funeral was seen as an indictment of official policy.

Clearly, football represents a risky proposition for rulers. Speaking to NPR Middle Eastern soccer expert James Dorsey noted the careful balancing act that some governments experience via sport. According to Dorsey, Middle Eastern football remains a “battlefield in which governments – certainly authoritarian governments – try to keep tight control of the game because the pitch is potentially, and often is, a venue for expression of dissent.” Recent events in Egypt, where soccer fans have disrupted games to make political statements</a>, illustrate that Dorsey’s reflections ring true outside of Iran as well.

Nonetheless, Iran’s government continues to use football as a means for its own ends. FIFA’s ban on the Iranian women’s team for refusing to stop wearing the hijab has given the regime a talking point about western corruption and bias. Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad called FIFA “dictators who just wear the gown of democracy.” Granted considering FIFA’s current state (corruption scandals abound with prominent periodicals like the Economist labeling the organization “rotten” and “awful”), any ruling by football’s governing body appears suspect. However, consider the fact that Iran continues to ban women from attending games and demands that its team wear a hijab and long pants. FIFA had been holding talks with officials to work out a compromise when a Bahrain FIFA official refused to allow the Iranian women’s team to take the field against Jordan. Of course, the New York Times noted that Bahrain’s own religious make up consists of a Shiite majority ruled by a Sunni minority. Sporting politics can tumble into transnational spaces. As for Iran, the Economist obituary frames the temptation of football succinctly: “Thanks in part to Mr Hejazi, Iran’s regime knows that the circus of the football stadium holds as many hazards as rewards.” Bread and circus are everywhere, but in some places, maybe they mean just that much more.

One comment

Pingback: Scattershot Politics: Sport and Its Serpentine Political Meanings « Scissors Kick

Comments are closed.